1. If Richard Holme were alive today, and if required to give an opinion on the current vicissitudes of Brexit Britain, I think he would say: Eaten bread must not be forgotten. The chief object of a Liberal Democrat is the equitable distribution of bread and the wellbeing of the country’s commonwealth; for social democracy is the essence of what it is to be a Liberal Democrat, we must never forget who we are.

The 2019 election – a seminal moment in British politics

2. In these anxious times of Brexit Britain, where people in the four nations in the United Kingdom are like the troubled sea which rages most when it dashes against a rock; I think Richard Holme would say that the key to navigating our way out of this nightmare is for every elected member of parliament to remember why they went into politics in the first place; it is certainly not to hanker after imperial glories past, neither is it for personal vanity. The 2019 general election is, without a doubt, a seminal moment in the history of British politics; indeed, it is impossible to exaggerate its gravity both to the United Kingdom as a nation, and to the rest of European Union. Because far from bringing years of much rage and frustration to an end, the 2019 general election may instead set in motion events which if not arrested at the earliest opportunity, have the potential to bring about the eventual destruction of a once-mighty country; this election may also act as the harbinger of the possible disintegration of the European Union dream. If the UK sneezes, Europe will most certainly catch a cold. And, as the Chinese say: These are interesting times.

The astonishing power of friendship

3. I am often asked by inquisitive people, how I managed to keep sane amid a very hostile environment in England towards immigrants, including refugees; after my candle was seemingly put out in the late 1980s, leaving me with no where to go. My answer has always been the same, and it is this: God did it all! Whenever I think about my experience as a refugee, I can’t help but thank God for the sweet providence – by which He saw to it that a little thing lighted up my candle again. That little thing was in the form of ‘friendships’ I enjoyed with many men and women in England whom God put in my path – friendships that were forged in the furnace of many trials and tribulations – which I experienced during the quest to regularize my status over a period of nearly 12 years. And, if it is true that I have subsequently become more English than the English as some friends are wont to tease me, which incidentally is not true; it is because of the influences of those whose characters informed my life in England, and none was more influential than Richard Holme. I was, as it were, a shabby desperado, but Richard did not think it below him to take cognizance of my affairs and show me kindness despite his elevated status; he kindly put a respect upon my person, and did me considerable honour; he for example took me to eat with him at his table. Thanks to his very resourceful private secretary, Ms. Chrissie Scanlan, Richard always found time to see me, despite his tremendously busy schedule. He was one of my many sources of intellectual stimuli; as he regularly supplied me with fresh published books and pamphlets touching on pressing issues of the day, which did much to keep the flame of hope alive.

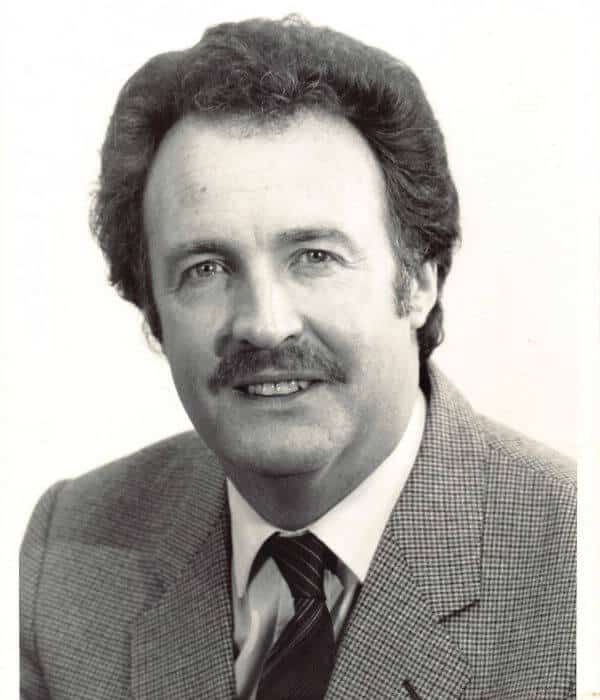

Richard Holme circa 1984

4. One summer afternoon in June 2007, as it happened, Richard Holme moved me to tears by his kindness. He went out of his way to see me for afternoon tea at The Cholmondeley Room and Terrance in the House of Lords; that meeting was shot through with much poignancy as he was gravely ill with terminal brain cancer, it was the last time he and I would ever debate together, he died on 4 May 2008. I remember the meeting as if it were yesterday; and most unusually for a man nearing the borders of the grave, he was full of beans, effervescing with many ideas as we leafed through a written proposal I had prepared, a collection of ideas which we had previously turned-over, and which subsequently crystallized into a seed idea for a venture I would later start following my relocation to Taiwan in 2013. I can still see his jovial face even as I write.

Social democrats have abandoned the Post-war consensus

5. Richard Holme could always be relied upon to make a worthwhile contribution to any new scheme, and he did so on this occasion; for he was a man whose primary stock in trade was ideas, with buckets of charm to boot. At his best, and I have heard it said of him often, he was the kind of man who could easily talk a bird out of a tree; he had an extraordinary comprehension of the more amiable weakness of human nature, which come to think of it, most probably gave him an edge in both politics and business. A quality, which no doubt made him almost indispensable as an advisor to political leaders of his heyday, that is, within the social democracy.

6. Speaking of which, and I hope you will kindly indulge me in saying that: if he were alive today, I think Richard Holme would most probably be the first to regret his own part in the catastrophic failure of leadership in the broad church of social democracy generally speaking. Because social democrats of all colours stand guilty for abandoning the Post-war consensus, which served our country well; for it oversaw the creation, among other things, a welfare state including ‘legal aid’ that is the envy of the world. In other words, social democrats have forsaken the dialectics which for long held sway between the two main opposing forces in British politics, leaving many ordinary British citizens politically alienated and at the mercy of a new virulent strain of the populist alternatives, on both the Right and the Left. It is worth noting here and now that, none of these populist alternatives have hitherto demonstrated a capacity to deliver practical solutions to existential and complex challenges we are all facing. Richard would probably call upon all social democrats, especially those of the liberal strand as characterized by the modern Liberal Democrat Party, to remember their pedigree. The Liberal Democrats are the direct descendants of the 18th century Whigs, who were famous for their public service to the nation, tolerance of religious difference, and protection of the people from all forms of institutional oppression. They were especially noted for believing that the commonwealth of Great Britain was better served by polite commercialism and the preservation of civil liberties.

7. As many in the British political establishment will remember only too well, Richard Holme was probably the most astute political strategist of his generation; he was a close advisor to David Steel, the Liberal Party leader (1976 – 1988), and his successor, Paddy Ashdown (1988 – 1999), following the formation of the Liberal Democrats in 1988. Richard was instrumental in the formation of the alliance with the Social Democratic Party (SDP), a splinter group from the Labour Party, with the Liberal Party in 1981. And in 1988, the two parties formally merged as the Social and Liberal Democrat, adopting their present name in 1989. For that reason, I believe he has as much right as any, to affirm that the Liberal Democrats should fight to defend their position in the centre ground of British politics, drawing from both Liberalism and Social democracy ideologies.

The pendulum has moved away from social democratic values

8. Keeping to the run of his possible advice that the Liberal Democrats should pay close attention to their ancestry, and considering his active involvement in Charter 88, including the all-party Constitutional Reform Centre in the 1980s; I think Richard Holme would argue that the advent of Thatcherism (also known in some quarters as the beginning of neoliberal capitalism) which manifested itself in the naked drive for more privatization, has caused the pendulum in British politics to swing away from social democratic values. And I fancy he would hope that following this Brexit debacle, that is, if we survive the fiery ordeal as a nation that the pendulum should somehow be nudged back in order to support ordinary British citizens in its sway. Truth be told, Brexit was long in coming; for successive governments following the fall of Margaret Thatcher competed to inherit her mantle, by the relentless pursuit of an economic Holy Grail which they hoped would bolster their place in running the UK Government, namely, by pressing for more deregulation, deeper financialization of the public sector, and affirming unrestrained globalization.

9. This reality coupled with the speed of change in the later part of the 20th century, it would appear to an objective observer that social democracy has over the years, bent over backwards to accommodate itself to globalization, instead of actually getting on top of the relentless march of change – by managing the said ‘change’ with pragmatic government regulation. We may rightly argue that social democracy has accordingly given in to a new political settlement which has seen globalization replace the political and geographical entity of a nation state, in that it is now accepted as gospel truth that because revenues of major multinational corporations are so vast, they have now been accorded the right to dictate terms to the government; thus many have come to believe, that the power of a multinational corporation is therefore greater than that of the government of the United Kingdom. The Google tax deal negotiated by George Osborne, the former chancellor of exchequer in the Tory-led coalition government several years ago, is but one such example to prove the point.

The unintended consequences of globalization

10. I remember as early as the 1990s Richard Holme trying to explain to me the phenomena of globalization. He was well qualified to speak on the subject seeing that he was for a considerable while, a man of affairs in international business, with interests ranging from publishing to a major mining conglomerate, the RTZ, which afterwards became, Rio Tinto. His business interests sometimes conflicted with his political endeavours; and, in 1996, for example, there was uproar within the Liberal Democrat Party, which led to his resignation from RTZ as its external affairs director. I think he defined globalization as the world-wide integration of markets, finance, trade, services, including culture; delivering many benefits to ordinary peoples across the globe. However, given developments in recent years, if he were alive today, I think Richard would probably be among the first to admit that the much-vaunted benefits accruing thanks to globalization have clearly failed to materialize; and where benefits are discernible, their distribution has not been equitable. A particular instance may now be mentioned to show how benefits have manifestly failed to materialize; the instance in question is in the realm of technology. Technologies such as the ‘World-wide web’ have been instrumental in the rapid march of globalization, they have made the world substantially smaller; but, alas, much of this technology is controlled by tech giants which have over the years accumulated immense power over data, that is, personal data as well as corporate information. I think Richard would say that the failure of globalization to benefit ordinary British citizens in particular is largely due to massive deregulation of finance and trade, which clearly put the interests of a corporate multinational over those of a citizen. This is a very good instance of significant failing on the part of social democrats.

Globalization – a poisoned chalice reference to immigration

11. Another instance in which globalization has had an adverse impact on England is in respect of the sensitive subject of immigration. Long has a feeling existed abroad that Britain is being overwhelmed by an apparent influx of foreigners from far and wide; and the onset of the full force of ‘freedom of movement’ which was in accordance with UK obligations under the European Treaties, made a challenging subject toxic. Local English men and women’s fear of immigration whether real or imagined, went a notch higher thanks in no small degree to peddlers of immigration myths and globalization in politics and in the popular press; these fears, which I confess are often exaggerated, went largely ignored by social democrats in successive governments of both Labour and Conservative, including a Tory-led government in which the Liberal Democrats were the junior partner.

12. Richard Holme and I debated the issue of immigration often, and we agreed that whereas it was not necessarily racist for one to feel threatened by difference; as we all fear that which is different from the familiar, at some point or other during our life-time. And yet, it is impossible to escape the unfortunate reality that our attitudes regarding difference have unwittingly given legitimacy to racism and antisemitism. These attitudes do not sit well with our understanding of that ancient golden rule of justice, to do to others as we would be done by. It was a matter of much regret for Richard that there was a conspicuous lack of leadership in the public sphere; the kind of leadership capable of formulating appropriate vocabulary with which to discuss immigration in a meaningful way. For example: The want of appropriate vocabulary has made it difficult to give a plausible explanation for the rapid changes which were taking place in England, within the context of immigration and globalization. What happened instead was the politicization and criminalization of immigration generally speaking; with the net result that each time the subject came up for debate, it often resulted in figuratively throwing the baby out with the bath water. This lack of leadership on this crucial issue has given the impression that the broader church of social democracy has abdicated her primary responsibility of protecting the interests of all British citizens, thus giving political space to the neoliberals to go town, by wildly playing on ordinary people’s fears. Immigration policy in England has something of a schizophrenic feel about it; it’s not healthy for a sophisticated country such as the United Kingdom of Great Britain, to espouse an immigration policy that fails to acknowledge economic realities on the ground, such as those in the NHS.

Globalization and tax policy

13. I believe Richard Holme would acknowledge that the broad church of social democracy probably went a little too far in the desire to be more in step with the relentless march of globalization. An instance comes to mind. I once challenged him on the seeming unfairness of policy in relation to taxation, namely, the continuous reduction in a rate of taxation on top incomes. After teasing me that I might be something of a closet Marxist, perish the thought that I should, he accepted that the concern had real merit; and drew attention to the phenomenon of a pronounced shift to a more aggressive tax policy-making on all things which are consumables. It flew in the face of pragmatic policy-making considering that we are largely a consumer society. This reality worried him, because it impacted most unfairly on the financially vulnerable in our society. The unfairness was made all the more pronounced by the perception, as noted above, that powerful multinational corporations, billionaires and millionaires, especially those engaged in industrial-scale tax avoidance schemes appeared to be given carte blanche; for such entities were in the enviable position of being able to move large sums of money from one jurisdiction to the next, and often or so it would appear, browbeat the government of United Kingdom to lower taxes even further. Looking back on events leading up that fateful Brexit referendum, I have no doubt that the failure to address this particular issue left many people in England extremely angry, and may have contributed to the decision to vote, ‘Leave.’

Globalization and privatization

14. Lastly, but not least, is the small matter of the privatization of Britain’s critical infrastructure – an idea which was ushered in by Margaret Thatcher. Whereas Richard Holme the international businessman could appreciate the value of greater involvement of private business in the public sector, on the grounds that business was probably more adept at discovering efficiencies and synergies; and yet, even he, at least by the time we had our last meeting, was beginning to concede that privatization of national assets in the UK had added little discernible benefit to the commonwealth of Great Britain. And over 10 years after his death, it is becoming very clear that the privatization project, at least in England, has been a major and costly distraction from the real business of sound government; that is, the proper management of national assets, including the development of sound public service philosophy, with a view of delivering value for money to ordinary British citizens. I once worked in the public sector soon after I was called to the Bar of England and Wales; during my time in the Thames Valley Magistrates Court Service as it was then, I remember how the ethic of administering justice slowly begun to give way to what is now known as the gig economy, thus eroding any remaining sense of ownership from the citizen’s point of view. By ‘ownership’ I mean the citizen’s ability to see that he or she is included in the script; that is, he or she is part of the process from start to finish.

15. This loss of ownership by the ordinary citizen is even more pronounced in other departments of government. Areas that should properly be in the realms of national security; the railway infrastructure being a good example, as it touches all aspects of the British citizens’ daily life regardless of what their social class is; the railway infrastructure has seen its assets auctioned off piecemeal over the years that trains are now the most complained of – because of their consistently delivering an unsatisfactory service to the public. I think Richard, without putting words into his mouth, would agree with me that aggressive privatization as experienced in the UK has failed in its original purpose; which is, to deliver efficiencies in service delivery. It has instead undermined the collective sense of citizenship and ownership in England, and most specifically, it has severely alienated the low-paid workers by exposing them to the full rigours of the market forces without necessary protection. This is not a plea for wholesale nationalization per se, but a call for better management of national assets for the benefit of the entire commonwealth of Great Britain.

16. As the Liberal Democrats are the direct descendant of the Whigs, I think Richard Holme would say that it is a matter of first importance for a British government to protect critical infrastructure from unrestrained privatization; for what has happened in the last 40 years in England would put to shame even the staunchest of free marketers. Successive governments in the United Kingdom have allowed substantial parts of the British state to be privatized; presiding over a gradual shift in government priorities from protecting British citizens’ rights to protecting the rights of the private sector, that is, favouring powerful multinational corporations such as pharmaceuticals, tech and data companies. No one would dispute that rights belonging to the private sector deserve legal protection. Indeed, our very own English common law has been and still continues to be at the vanguard in the development of patent law; for patents serve a useful purpose in protecting the legal rights of inventors, whose ideas have been instrumental in making all our lives so much better; their innovations should therefore be encouraged and rewarded. However, the exponential growth in patents, trademarks, copyright, including industrial designs; has had the unintended consequence of creating monopolies such as large pharmaceuticals, whose only interest is the maximizing of profit at the expense of the interests of the British citizenry. This must change.

Who was Richard Holme?

17. But who was this remarkable man, Richard Holme, whose memory I am here esteeming? Richard Gordon Holme was received into this world on 27 May 1936; at No. 19 Bolingbroke Drive, Battersea, in London. He was born into a family steeped in public service, as the only son of Jack Richard Holme, a Freemason and a detective constable in the Metropolitan Police; and his mother, Edna Mary Holme, nee Eggleton. His childhood was however marked indelibly by tragedy, which caused him to walk in the hospital of life right early; for he was barely a toddler, when his father, a lieutenant in the Intelligence Corps, was killed in action in 1940, during the Second Great War. The young Richard Holme was educated at the former Royal Masonic School for Boys in Bushey, Hertfordshire. He did his national service in the 10th Gurkha Rifles in Malay between 1954 and 1956, as a lieutenant; and while still doing his national service, Richard joined St John’s College, Oxford – where he read jurisprudence.

Serendipity at Oxford

18. At Oxford, two significant serendipitous events happened to Richard Holme that changed his life forever. The first event was falling under the extraordinary influence of Joseph Grimond. Joseph Grimond rose to fame after capturing the Orkney and Shetland parliamentary seat for the Liberal Party in the 1950 general election. The parliamentary seat is the most northerly constituency in the United Kingdom; it has remained in Liberal and their successors, the Liberal Democrat’s hands to this day. Jo Grimond, as he was fondly known, was a remarkable man, with considerable charm and intellect, a gifted public speaker as well as an author; he led the Liberal Party from 1956 to 1967, during his tenure the Liberal Party was transformed from something of an inconsequential political party into a notable political force by doubling its tally of parliamentary seats. The party, for example, won a historic by-election at Torrington in 1958 – a first by-election gain in 29 years. This success was followed by other impressive wins, namely, winning the Orpington by-election in 1962, which was reckoned by some as the beginning of the Liberal revival; the Liberal Party also won other by-elections in Roxburgh, Selkirk and Peebles in 1965. It’s no wonder that Jo Grimond’s charismatic but principled leadership proved such an irresistible magnet to ambitious young aspiring politicians to the Liberal cause, of whom David Steel, the late Paddy Ashdown and Menzies Campbell were but a number. It was to this group that Richard joined by formally becoming a member of the Liberal Party in 1959. The second significant event was falling in love with a daughter of a surgeon, who went by the name of Kathleen (Kay) Mary Powell; they married on 4 July 1958. An extraordinary woman in her own right, Mrs. Kay Holme’s beauty and character were surpassed only by the enduring ballast she brought to Richard’s life.

Richard and Kay Holme circa 1987

Some men are born with a beard

19. Richard Holme graduated from Oxford with a second class law degree in 1959, but there was nothing second class about him at all. He was wise beyond his years; beard and all. Ever the practical man and considering that he was now a married man, Richard prudently elected to go into business, instead of following more prestigious openings that were available to him. I well remember how much he teased me about accomplishing something he had not been able to do, that is, get called to the Bar of England and Wales. He took marketing posts with Lever Brothers and afterwards Cavenham Foods in 1959. But quickly moved into publishing, something he had always wanted to do, by first accepting a role as a marketing director at Penguin Books in 1965; moving two years afterwards to join the British Printing Corporation’s Books division, and was subsequently appointed chief executive with a seat at the BPC board of directors in 1969. During this time, he even managed to squeeze in time to read for and graduate with an MBA from Harvard Business School.

20. Although clearly busy at establishing himself in business, Richard Holme did not neglect his political interests. In fact, his political fortunes rose spectacularly within the Liberal Party. So much so that the Liberal Party put him forward to contest the parliamentary seat at East Grinstead in the general election of 1964; he was not successful. He was put forward again in a by-election the following year; and failed to win the seat again. Richard served as the Vice-chair of the party executive from 1966 until 1967 – the year in which Jo Grimond, who had led the Liberal Party through three general elections, decided to give way to a much younger and more charismatic leader, Jeremy Thorpe, the Liberal Member of Parliament for North Devon, as he was then. Perhaps it was his legendary political nous, but it appears Richard had the foresight that perhaps the Liberal Party’s fortunes would not fare well under the leadership of Jeremy Thorpe; and with the opportunities beckoning him overseas, plus the fact that he was at a sprightly youthful age of 45, he reckoned rather wisely, that there would be time plenty enough for him to take a break from active politics, with a view of returning and take up the Liberal cause later. Thus it was that he elected to relocate to San Diego, California, to take up a position as Vice-president of a publishing company in 1971.

The pioneer in a hurry

21. His sojourn in the United States of America did him a power of good; because it was in the USA that he became established as a man of independent means, capable of supporting his young family of two daughters and twin sons in comfort. Richard Holme returned to Britain in 1974 to try his luck at entering parliament and to concentrate on advancing the Liberal cause. Thus it was that in the general election of October 1974, Richard fought the parliamentary seat of Braintree, which, alas, he did not win. It was as well he did not win the seat: for unbeknownst to him, his fortunes were about to enter probably the most productive and consequential period of entire political career; commencing with establishing a Campaign for Electoral Reform in 1976, which he directed for 9 years. He served as president of the Liberal Party from 1980 to 1981; and set up a think-tank, The Centre for Constitutional Reform, which lasted from 1985 to 1992. He even managed to write a number of books and pamphlets, including No Dole for the Young (1975), A Democracy which Works (1978), and The People’s Kingdom (1987); and he was also the joint editor of 1688-1988: Time for a New Constitution (1988). But his pioneering endeavours at constitutional reform were eclipsed by more impatient and radical pressure groups such as Charter 88, which captured the imagination of the entire country, following the 1987 general election victory by the Conservative Party under the leadership of Margaret Thatcher, the then British Prime Minister. Not wishing to be left out of the march of events, Richard threw his lot in with the 347 intellectuals and activists behind Charter 88 pressure group; becoming the founding joint council chair along with Stuart Weir, the journalist, from 1988 to 1989.

Richard Holme, Andrew Pennington and others supporting a strike by GCHQ at Cheltenham circa 1984

The cobbler’s wife goes barefoot

22. Richard Holme was a rare breed, an outstanding Liberal activist; best known for his prudence. Although there are well documented instances in which the occasional flash of temper would be visible for all to see, he was in many respects something of an anvil; he wore out many political hammer blows by his indomitable patience, especially during the time when the Liberal Party experienced a season of internal turbulence, leaving the party looking like an eel. Understanding that worms, including glow-worms, if made to speak as one, are a force to reckon with; Richard worked tirelessly to put into the Liberal Party some backbone, thus transforming it from a debating society to an actual political party capable of exercising influence on the national stage. This was the time when Jo Grimond, who had experienced success during his previous stint as leader, was called back to lead the party again after Jeremy Thorpe was forced to resign in 1976, following a scandal; to hold the fort until a new leader was elected. Richard and Jo Grimond were similar in more ways than one; they both shared a longing for a Centre-Left realignment in British politics, and in that sense Richard was probably the true inheritor of Jo Grimond’s mantel. It was during this period of political turbulence that Richard became a dedicated day-by-day unpaid special adviser to the party’s leaders; he was not only instrumental in the election of David Steel as the next Liberal Party leader, but was also a permanent fixture in the party power structure, making him easily the most influential Liberal Party spokesman for nearly 30 years.

Richard Holme and David Steel on the campaign trail at Cheltenham circa 1987

23. As I have indicated above, Richard Holme always carried about him a store of the current coin in the art of connecting people, ready for exchange on all occasions that he was never at a loss when the opportunity for using it presented itself. Thus it was that while we were enjoying our last afternoon tea together in 2007, Lord Steel of Aikwood happened to pass by, and in that moment Richard reached out to him, insisting that he join us in order to formerly introduce to him a fellow African man he had mentioned a while earlier. That was the first time I met David Steel in the flesh. I had heard a great deal about him, and Richard sometimes referred to him as the honorary African man; for David Steel spent part of his childhood in Kenya. When I recently got in touch with Lord Steel for a possible anecdote, he remembered Richard Holme with a great deal of warmth. Lord Steel recalled the pivotal role Richard played in the formation of an alliance between the Social Democratic Party and the Liberal Party, and this is what he said: “At the Konsigswinter conference in Germany we dined with Shirley Williams and Bill Rodgers to discuss the formation of the Liberal-SDP Alliance. Richard wrote our conclusions on a paper napkin which became known as the ‘Konsigswinter compact’ and was hugely influential in getting the Alliance going much to the annoyance of David Owen.”

24. Those familiar with mergers and acquisition in the business world know only too well, the skill required to decipher the underlying principles which form the most important part of managing such transitions, may be able to form some idea of the challenges involved in presenting a brand new political party to the British public. Lord Steel especially remembers an instance, during the teething period of the alliance, which he put thus: “At the Croydon by-election we had a rather inadequate candidate and Richard volunteered to “mind” him which he did by not allowing him to answer questions at the daily press conferences and drafting his speeches. He later complained to Bill Rodgers that he had failed similarly to “mind” the inadequate SDP candidate at the Darlington by-election, which (unlike Croydon) they lost.” However, for all his political nous, Richard Holme somehow failed to win a seat in parliament in his own right. In addition to the three previous occasions mentioned above; Richard, despite having very good credentials and prospects as the Liberal and then as the Liberal Democrat candidate, he nevertheless failed to win a seat in parliament in the general elections of 1983 and 1987 at Cheltenham. He was a real contender at his last time of asking, but failing to overturn a 5,518 Conservative majority at Cheltenham was particularly disappointing to him personally, thus making our common English proverb, the cobbler’s wife goes barefoot true; for he that shod others with magnificent Liberal Democratic shoes, was left without appropriate footwear. All the more ironic, that after throwing in the towel as it were, the Cheltenham parliamentary seat was actually won by a Liberal Democrat in 1992.

Drawn wells have the sweetest waters

25. It is often said that failure is an event, and not a person. Richard Holme’s failure to win a seat in parliament did not diminish his prospects however. On the contrary, he prospered as an endearing man; for he cut a figure which was instantly recognizable with his erect military bearing complete with a moustache, his good looks and elegant presentation in attire were surpassed only by his warmth and charm. Indeed, he was something of a drawn well; the more goodness that was extracted out of him the sweeter his waters became; he was an exceedingly serviceable man to his party in particular. He continued to give invaluable counsel to the leadership of the party, even after Paddy Ashdown succeeded David Steel as the Liberal Democrat Party leader.

26. Speaking of Richard Holme’s usefulness as a counsellor, a special instance may now be mentioned. I remember it well. One melancholy evening in 1992, as it happened, the tabloid press caught wind of a story concerning some stolen documents about a divorce case. The documents identified the Liberal Democrat leader, Paddy Ashdown, to have had a five-month affair with his secretary, Patricia Howard, five years earlier; from which he had earned the notorious nickname, ‘Paddy Pantsdown.’ Now no political crisis is ever welcome, but this one came on a bad issue and at a wrong time; for the Liberal Democrats were in a high state of preparedness for the high-stakes 1992 general election, expecting a hung parliament in which the party would get to play a significant role. Such was the high-wire act at this general election, that some in the party even feared a possible annihilation, that is, if things went horribly wrong for the Liberal Democrat Party. There was only one cat in the entire party that had the dexterity of rescuing the leader’s reputation ‘chestnut’ from the ensuing political firestorm, Richard Holme. And it was to him that Paddy Ashdown turned. Richard immediately went to work, taking control of the situation, and advising Paddy Ashdown to come clean by way of a statement, in order to defuse the scandal. There was a late swing which gave John Major’s Conservative Party an unexpected win. Paddy Ashdown lived to fight another day, surviving the political firestorm in the process, including his wife forgiving him. Unlike the cat in the fable, this particular cat’s paw was not scorched in the process; his endeavours were suitably rewarded.

Lord Holme: a man of considerable affairs

27. Having been appointed a CBE in 1983, Richard Holme was made a life peer, as Baron Holme of Cheltenham in 1990; Paddy Ashdown rewarded Richard by appointing him the Northern Ireland spokesman for the Liberal Democrats in 1992, a portfolio he fulfilled with much assiduousness and authority for a period of seven years until 1999. And as a member of Paddy Ashdown’s inner strategy group, Richard went on to manage the Liberal Democrat’s general election campaign of 1997, including overseeing talks between the party and New Labour Party, in event of a hung parliament or of a small working majority under Tony Blair. A pre-election agreement was duly entered into between Robin Cook and Bob Maclennan, thanks in no small degree to Richard Holme and his New Labour counter-part, Peter Mandelson. But, alas, the subsequent New Labour landslide put paid to the Lib-Lab pact, and with it went any hopes of Richard’s possible political advancement. Not all was lost however, as Richard, in his capacity as Liberal Democrat party chairman, superintended a successful campaign in which the party doubled its numbers in parliament to 46 seats; the largest number since the 1920s.

28. Moreover, having taken part in the pre-election coalition talks mentioned above, Richard Holme was one of the five-strong Lib-Dem team that sat on the Lib-Dem – Labour joint cabinet committee between 1997 and 1999. He had the unusual pleasure of seeing many of the constitutional reforms he had advocated for over many years implemented. Most notably, he lived to see proportional representation respecting the European Parliament, Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly; accepted by New Labour, notwithstanding Tony Blair’s seemingly unassailable majority in parliament.

It is impossible to keep a good man down for long

29. We have all need to walk circumspectly, because we have many eyes fixed upon us, including some that watch for our stumbling. Thus when Paddy Ashdown resigned the leadership of the party in 1999, to be succeeded by Charles Kennedy, Richard Holme thought it best that the time had come for him to step back from his role as counsellor to leaders of the party. He however continued to be active in public life, accepting a role as deputy chairman of the Independent Television Commission; a stepping stone to the full chairmanship of the Broadcasting Standards Commission. And, just as the year 2000 was proving itself to be something of an annus mirabilis for him, after Richard was sworn in as a member of the Privy Council; alas, it quickly descended into, what looked to many, something like an annus horribilis when calamity struck, following the News of the World expose` on him with revelations about an extramarital affair. Richard had no choice but to resign his coveted chairmanship of the Broadcasting Standards Commission; something he did very quickly.

30. Those that show mercy to others, mercy shall be shown them. The above humiliating expose` left Richard Holme looking like a shorn lamb put out to grass; but such was the regard many in the business world and politics had for him that much mercy was shown him, many friends continued to trust and respect him, and in the process they tempered that humbling vehement wind from the East, which should have otherwise crushed him. The year 2000 was not the annus horribilis many feared; to the relief of all those who loved him. He was quickly rehabilitated with chairmanships of Globescan, LEAD International, the Lords’ Select Committee on the Constitution from 2000 to 2007; and, the Hansard Society, also from 2001 to 2007. His educational interests ranged from the chancellorship of the University of Greenwich, chairmanship of the governors of the Ladies College Cheltenham, to schools projects in both Europe and Africa.

31. This is perhaps a good place to end this short biographical blogpost on the life of an extraordinary man. However, I beg your indulgence, if I may, to share with you one more anecdote to sum up; it’s a little cherry on the top. As daylight can be seen through small holes; little things illustrate a man’s character. One dreary morning in the late 1990s, I telephoned Richard Holme’s private secretary, Chrissie Scanlan, at his London office to arrange a possible meeting. I was astonished to discover that he had just stepped out in the pouring rain to call at his bank branch in the city to sign my student loan papers; Richard, together with Paul Baker, a prominent Cheltenham businessman, stood guarantor to help me through Bar School in London. Accordingly, my abiding memory of Richard will always be his determined resolve. I am persuaded that this is the sort of resolve we must all have, if we are to force our way through the irksome drudgery of a tumultuous Brexit Britain. Thus in remembering the bread I ate with Richard Holme, I am sanguine that all will be well in due time, in the best of times.

Editor’s note of acknowledgement and credit:

The photographs featured in this blogpost are by Phillip Gray.